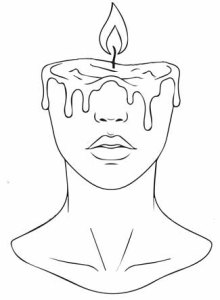

The Mother Made of Wax at Dawn

The Mother Made of Wax at Dawn

by Meredith A. Bak

It happened one autumn morning. For the rest of his life, the boy refused to disclose what he had seen in the early gray light during the milking and churning and emptying and filling chores that revealed to him that his mother was made of wax. Without thinking, he bolted for the emergency bell that hung from the post near their door. Every household had such a bell. They were ordinarily rung only in times of duress. When something was on fire. When a baby was stuck in the birth canal. If an invading army was spotted cresting the distant hills. As soon as the clapper sounded its frantic clang, rousting neighbors from their own somnambulistic morning routines, there was no taking it back.

The initial commotion was mixed. A few ladies wept and threw themselves on the ground as the mother was carried from the house, as though it were a religious event. Earlier that year, they had found a few saints’ teeth in a well two villages over and everyone was still amped up about it. Other neighbors shed their grogginess for contempt. They arrived prepared to jeer and taunt, like they’d slept with rotten tomatoes in already-clenched fists.

***

When it was something as cut-and-dried as a woman actually made out of wax, there was no need for even the pretense of a trial. The local magistrate made note of it in his personal diary only as a curiosity, as when he’d seen a comet streak across the sky, or that spring when there were so many frogs. The decision was made to melt her down and remold her into tapers. It was practical, but her children were very emotional when they heard.

Suddenly, all the compliments the mother had ever received—on her flawless, alabaster skin, her expression of perpetual serenity—were now marks against her. She’d never been much of a cook, claiming she preferred to feed her family the fresh fruits of the field when they were in season than to boil them down to mush. She hadn’t wanted to cook over the open hearth.

“No one ever asked me if I was made of wax,” was all she said before she dissolved in the crucible.

Afterward, the father was followed by a shadow of impropriety, as though he’d done something untoward by marrying a woman made of wax. But how was he to have known?

***

It was hardest on the children, of course. The daughter, the older one, was just readying herself for her debut, the dowry chest lined with cedar planks and repacked for when the time came. Now she’d be expected to pick up the slack around the house. Her posture would suffer. She would get pruny dishpan hands. There would be gossip about whether she, herself, was waxen. These rumors would surely dissuade the right kind of suitors and attract the wrong kind. She imagined fending off paunchy middle-aged men with horse breath while all the hale farm boys pursued maidens from neighboring hamlets. The boy, now freighted with guilt, put in extra time at the guild hall and would eventually lose several fingers and toes in occupational accidents owing to his lack of sleep. The dawn hour was a haunted time for him now. No matter the time of year, he was awake when the first rays of sun pierced the grimy glass window in the keeping room. Was it something about the quality of light that tipped him off that morning? He wouldn’t say. His own face took on a waxy sheen that he interpreted as an inheritance of sorts.

***

An auburn fall turned into a brittle winter. The father and the two children fell in with the less-desirables. Widows whose faces swarmed with bulbous growths. Farmers who kept suspicious-eyed goats. Poultice-makers. Sundays were especially difficult. The story of the wax mother was generative for the minister, who made and remade her tale in the shape of Eve’s transgression, Jezebel, and—the easiest fit—Lot’s wife. He delivered these lessons in hardly veiled terms each sabbath, which put a lot of social pressure on the father and the two children. They started sitting near the rear of the church, even though the statue of the virgin looming over them back there was somewhat triggering. In the weeks after heavy rains destroyed the rye crop, the church’s stone walls wept, producing an earthy smell that even incense failed to mask. Light from the candles affixed to the damp walls flickered along the contours of the nave. The boy, his mangled, shortened fingers in various states of healing, could no longer hold the hymnal. Instead of singing, he spent the service scouring those walls, searching for light thrown by his own mother shining back on him.