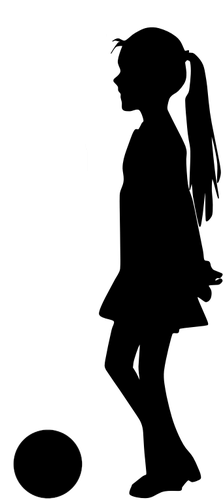

The Last Little Girl

The Last Little Girl

in Ponca City

by Chris Panatier

The shadow cast by the weeping willow was dark enough that the sun didn’t burn her skin. Sadie sat on the bank of the pond watching a log over which dozens of turtles had piled themselves. The turtles didn’t know what had happened to the people. They probably wouldn’t care. Sadie envied the turtles. There were so many of them, they’d never be alone.

The sun dropped away and Sadie stood from the grass to set out for her nightly wandering. She walked to the school she’d once attended and sat into a swing on the playground. The chains creaked up and down, and she pretended the moon was a ball, bouncing on the schoolhouse roof. The moon was lonely too. Sadie sang it a song.

When it was over, she gave voice to the moon. “Thank you, Sadie,” she said.

“You’re welcome, Moon. I love you,” she answered.

“I love you, too,” said Sadie to herself.

She left the playground to search for people, though she knew there were none, but the ache of loneliness was deep and that made her hold on to hope. There was a lopsided soccer ball out on the street. She kicked it once each night, moving it further and further toward the outskirts of town. If she didn’t find anyone soon, she guessed that she’d have to kick that ball all the way east to Bartlesville, where she suspected the people who’d gotten away had gone to hide.

If she didn’t find somebody soon, the hollow in her belly would swallow her whole.

Going past the old dairy plant, she came to a wall of mirrored steel and stopped to chat with the little girl who looked like her, walked like her, but never spoke unless Sadie spoke first. Sadie recognized herself, though she’d changed since everyone went away. She was dirtier and her hair was tangled and her pupils flickered orange like pumpkin light. The little girl in the steel had been fading in recent days. Their tummies grumbled.

There were fish and birds, and even the turtles, but they wouldn’t do. Nothing that might have done in the past would do now. The days when her parents cooked dinner each night seemed like another lifetime. She’d watched them die and had sat beside their bodies until the hollow returned and got her moving again. She hadn’t gone back to the house since.

She came to the body of a little boy, recalling vaguely the day he’d fallen. He had been too slow when others were fast. There were many more like him. Sitting onto the concrete opposite, she pressed her feet to the soles of his shoes. The size was close enough. She removed his sneakers and laced them onto her feet.

She walked all night. It had been days since she’d found anybody alive. The last one was an old woman Sadie had stumbled upon in a special home for grandpas and grandmas. Sadie had rejoiced at the time, thinking it meant there would be others, but it was just the one, and she had been small and shriveled. What little Sadie could get only left her craving more.

At dawn, she arrived at the pond exhausted, and settled into the deep shade of the willow tree and slept. Fatigue came quicker nowadays, and her sleeps were longer and longer. She would leave Ponca City in the evening and follow the signs to Bartlesville. She couldn’t stay here.

Her slumber was dreamless and complete. Not even the ducks and geese with their honking disturbed her. It was after dark when she rose again. The animals were gone. She’d planned to wish them a happy life.

Since she was leaving town, she decided to visit home. There, she stood over the bodies of her parents and her big brother Jason, who’d been the third to die. She didn’t know what to say to them. “Sorry” felt wrong.

At the park she swung and said goodbye to the moon. The moon wished her luck and said it would watch over her. The soccer ball was where she’d left it and she nudged it along, for it was her only companion and she would bring it with her.

The buildings and homes thinned out. The sign for the city limits came and went. Then it was just highway with the wide-open prairie on either side.

After many miles and many songs sung to the night, Sadie halted in the center of a crossroads. Another little girl stood upon a rise in the distance like an exclamation point. Even with the space between them and the darkness of night, Sadie saw that her eyes had the pumpkin light.

Her heart went full and bouncy like a water balloon.

The new girl made her hands into a bullhorn around her mouth and hollered, “Where do you come from?”

Sadie cupped her hands into her cheeks. “Ponca City! Where do you come from?”

“Bartlesville!”

If she was coming from Bartlesville, then no one else was alive there. Sadie guessed this girl had hiked to Ponca City for the same reasons as she had set off for Bartlesville. “There’s no one left in Ponca City!”

“Where should we go, then?” shouted the new girl.

Sadie considered the signage. “Sign says Fairfax is seven miles that way.” She pointed south.

“Okay.”

The girl began walking again. Sadie waited at the crossroads until they were face to face. They considered each other for a time, eyes flickering like jack-o-lanterns.

“I’m Sadie.”

“I’m Rachel.”

Staring into Sadie’s eyes, Rachel came closer. It made Sadie a little scared, but then Rachel’s arms were around her and Sadie’s were around Rachel, and they hugged in silence as the night crickets whistled.

Then they headed south under a watchful moon, kicking the old soccer ball in turns.

![]()