What to Do When

What to Do When

Your Loved One Is Abducted

by Emily Livingstone

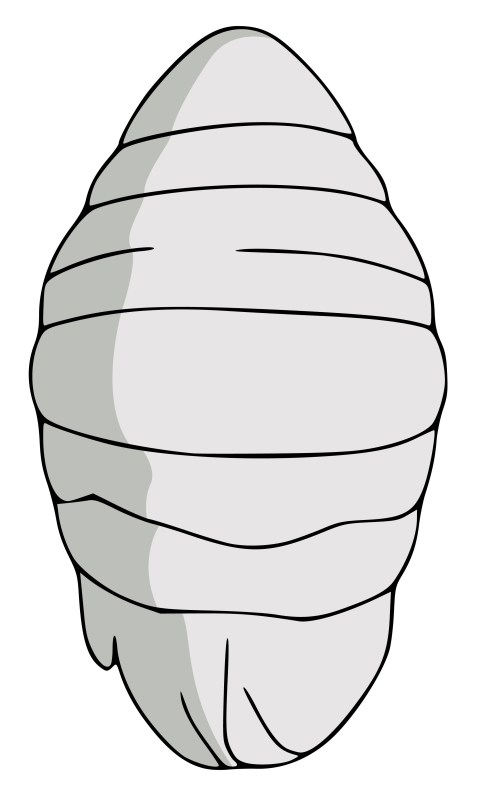

I step out of the cocoon, then help the kids. They’re droopy and quiet. The cocoon shrinks down until Jack’s shape is clearly outlined in the strange skin. It’s smooth on the outside, but inside, it’s furry and warm.

I turn on the TV. I sense tonight will be one of the nights. I don’t feel good about the TV or the cocoon, but they don’t exactly have a manual for this. That’s why I’m writing one.

I stroke the cocoon where his cheek is. The cocoon’s roots have grown into the ceiling and floor of the living room. The aliens installed it during the first abduction. He spends more and more time there.

I bring the kids outside. The two-year-old splashes her hands in a puddle. The four-year-old piles sticks.

I open my laptop:

People may judge you for sleeping in the cocoon with your loved one, but they haven’t lived with an abductee. Burrow in without shame.

Around five, Jack comes out. The cocoon shrivels into a blood-colored vine.

“Daddy!” the kids shout.

He blinks.

He eats mac and cheese, laughs at the kids’ jokes.

Though your loved one looks mostly the same, be patient. The abductions make the mind wander. They cause fatigue, headaches, nausea. There is a tendency to speak a strange language, which the aliens say is a treatment side effect.

We bathe the kids and read stories. Only once, in the middle of a story, does he say, “Harangliton brafnit.”

On the couch, we snuggle close.

Around 9:30, the lights go out. The room glows. I grip his hand, and he squeezes back. They are all five feet tall. Tentacles emerge from their sides, then manifest tools. They wear white, like our doctors.

The aliens, when they’ve chosen to speak, say they are treating a deadly disease. There have been no verifiable diseases found by human doctors in abductees.

I hold Jack’s hand as his shirt disappears. The alien nearest us lays a tentacle on Jack’s chest, melding it to his body. Jack’s skin turns purple then orange, alternating rings of each color, like ripples in a pond.

This alien, I think, is called Fopnayix. Fopnayix has kind eyes. Some have cold ones. Some, no eyes at all.

Jack groans, and Fopnayix nods, maybe in sympathy.

I ask, “Is it working?”

Silence.

Like many of you, I’ve tried preventing the abductions.

They always find him. When the abductions begin, weapons disappear. When the abductee tries to leave, the aliens use their tentacles.

Readers, if you discover how to prevent abductions, please contact the author.

Finally, it’s over.

We climb into the cocoon and cling to each other until morning.

I still have to go to work, so I do that.

For those of you balancing family, work, and abductee care, remember that you are only human (though perhaps your loved one is not—a little abduction humor). Remember to take care of yourself.

When I get home, I see my brother-in-law’s truck, tailgate open. Luke’s in the house, sawing at the cocoon’s ceiling tether. I scream as if he’s cutting into me. Or like Jack did during the first abduction.

I’m running, but already Luke’s easing the cocoon to the floor.

“I’ll take care of everything,” Luke says. “He’ll be in the family plot.”

Clenching my jaw, I open the cocoon, touch Jack’s warm cheek, call his name.

“No!” Luke says, grabbing my wrist, but once Jack’s eyes open, he lets go.

Dealing with family and friends can be difficult. Remember, they are also experiencing strong emotions.

Jack and I nail the cocoon to the ceiling as best we can. It reminds us of when this all started. Jack rubs my back. I lean into him.

A bit of history: the abductions began four years ago. No abductees have yet died from disease or during abduction. Some think the abductees brought this on themselves. Some think there are no abductions, only scammers. Others believe the aliens are saviors.

We go out to dinner while my mom babysits. Jack’s skin waxes green as we eat. He puts his hand over mine, and we toast what’s still ours.

Afterward, he’s tired. He enters the cocoon, holds open the flap, but when I get in, it starts to separate from the ceiling. We go to our bed. He wraps himself around me, and we feel air all over us, so giddy and free I almost can’t sleep.

When I wake, he is shivering, purple-tinged. I help him to the cocoon.

The next morning, I call the kids for breakfast.

“Wait—for—Daddy!” they shout, but the cocoon is quiet.

Jack meets us in the yard later. The kids brew him concoctions from their playhouse, shoveling dirt into cups.

Then they’re screaming.

Jack swipes a hand across the belly of the younger one and up to his mouth.

The screaming stops.

“Daddy ate the bee,” the other says. “Silly Daddy.”

Your loved one may have vivid dreams, alterations in skin color, and changes in diet. Remember that your loved one cannot help his new cravings. A caregiver will inevitably wonder, what symptoms are next? Will he still know us? Will he still kiss me passionately, and will it be with a human tongue?

Late Sunday, the feeling of abduction is in the air again. Jack cocoons. I sit on the floor beside him.

You ask, when will it end?

There have been no reports of abductions stopping in those abductees who still live.

I feel the cocoon’s pulse radiating outward. I imagine it’s his heartbeat, not some alien thing. I press my fingers to my wrist and breathe, trying to match the rhythm.