Daddy’s Girl

Daddy’s Girl

by Colin Alexander

The pink neon hand with the blue winking eye typically drew unmoored seekers like moths, but as water sizzled on its flickering surface, Sylvia considered closing early.

Rain was one of the few things Sylvia couldn’t talk her way out of, and just as she reached for the keys to lock up, the bell above the door tinkled.

The woman had deep circles under eyes packed with foundation. She wore a thick black coat with subtle green threading, and an emerald on her index finger heavy enough to drag a rat to the bottom of a lake.

Her eyes shifted in the candlelight, at once gray then green, then almost purple. The only thing Sylvia could say for certain was they were brimming with tears.

Sylvia’s father, Vincent, would have said the woman “showed promise.”

He fondly referred to the shop’s entrance as “the funnel of fools.”

“Some are good for a reading or two,” said Vincent, using the staccato rhythms of Brooklyn Italian instead of the vaguely eastern European accent employed for customers. “Others will buy black candles to ward off evil. But the most desperate, the most bruised by circumstance, will cut their own veins to escape fate.”

He’d taught Syliva how to fish for information, dazzling rubes with Barnum statements that sounded specific but applied to everyone who walked upright.

“You’re seeking answers about love or money.”

“How did you know?” they’d respond, suddenly gushing, providing details Sylvia’d squirrel away for later “premonitions.”

Everyone was seeking answers about love or money.

She’d shotgun them with predictions, polishing the hits and varnishing the misses, building their confidence in her mystic talents.

“Sometimes, you doubt whether you’re on the right path.”

No shit.

“Most important,” her father reminded Sylvia, “is the story. The more information gleaned, the more precisely you can weave their hopes and desires into it.”

“And then we gut them like a fish,” said Sylvia, shuffling a deck of tarot cards like gravity didn’t apply, a card spring forcing the colorful portraits to swim from her hands.

“Then we gut them like a fish,” repeated her father proudly, cracking a pistachio in his hand, popping the meat into his smiling mouth.

“I’d like a reading,” said the woman with the emerald ring, shrugging off her purse, searching for a sign listing the cost of services which didn’t exist. The cost, like the story, was tailored to the customer.

Sylvia extended her upturned hand, guiding the woman towards the back of the room where candles burned perpetually.

They spent a fortune on candles.

Of all the tricks her father’d taught Sylvia, she’d surpassed him in only one: tarot. She could turn any card and seamlessly weave a tale, turning Death into transition, The Devil into desire, or The Ten of Swords a painful cycle ending, birthing a fresh start.

“The cards never matter,” Vincent always said. “Just the story.”

“You’ve experienced a significant loss,” said Sylvia, placing the well-worn tarot deck atop a circular wooden table. She hated the glass orb at the center of the table, but her father insisted it was as necessary as the candles for setting the scene.

The woman’s mouth tightened between a wince and a smile, and Sylvia nodded.

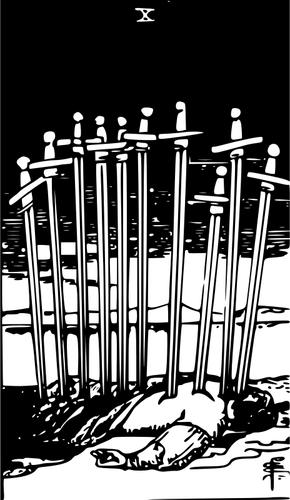

“Focus your intent,” said Sylvia, shuffling the deck with one stiff pinky finger, forcing the same three cards to the bottom so she could dole them out on cue: The Tower, The Ten of Swords, and The Devil. Sylvia could spin a story from whatever cards fate drew, but wouldn’t turn down a well-timed dancing skeleton from the bottom of the deck.

“My father,” whispered the woman.

Sylvia dealt three cards, face down. She dealt The Devil last, from the bottom of the deck, taking whatever chance gave her for the first two cards.

“Past, present, future,” said Sylvia, pointing a long red nail at each card.

Sylvia turned The Ace of Pentacles, and was surprised when the customer spoke up before her.

“Recently came into money,” said the woman, her eyes gray.

Sylvia had, in fact, recently made a particularly big score off an old man, enough she’d considered giving up the shop and cashing in. But the business was her father’s life.

This was still Sylvia’s story to tell, however, and she’d anchor it around the second card.

She turned The Devil.

Sylvia’s mouth opened and closed like a trout. She’d placed The Devil third, and seeing it second set her on her heels.

“Deceit,” said the woman, eyes flashing green.

“If you’ll just allow me…” Sylvia reached for the third card, still confident she could build the wings of a story while falling.

The Ten of Swords. A card that should have still been buried at the bottom of the deck.

Sylvia couldn’t have fouled a deal so completely. Could this be the woman’s grift?

“Death,” said the woman, nodding to the rusted swords. “But the card can be read several ways. It could refer to your death, or the man you stole from.”

“I didn’t…” said Sylvia, staring into the woman’s purple eyes, realizing she’d forgotten how to lie.

“I didn’t know he was dead,” said Sylvia.

“Grief will do that,” said the woman, standing.

“Which is it?” asked Sylvia. “His death or…”

“Neither,” said the woman, smoothing her coat. “He was an old man, and the world demands balance.”

Sylvia avoided the woman’s burning eyes, staring instead though the glass orb at the center of the table, inverting the backlit figure framed at the threshold of “the funnel of fools.”

A quiet fell over the candlelit room, and from the doorway, the whites of the strange woman’s eyes disappeared, leaving only darkness.

One by one, dozens of candles around the room extinguished until only one remained.

“Who…” said Sylvia, but she was cut off by the bell of the antique telephone in the back.

The woman turned towards the door.

“Pick it up,” she said, striding out. “You’ve recently experienced a great loss.”